- Home

- Michele Filgate

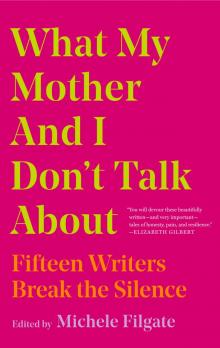

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About Page 7

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About Read online

Page 7

This testimony is good practice for when I don’t tell about the night my friend called, begging me to tell him he wasn’t like me, that he wasn’t gay. Telling me he had a shotgun, his dad’s, and was ready to kill himself if he was. Tell me, he said. Tell me I’m not like you. And I do. You’re not like me, I say. You’re not gay. We’ve spoken of it at last. Because isn’t it better to live? For him, at least. I don’t say all the times I almost tried, staring at the knife in the kitchen, so often as I made the food, wishing I had the courage to go upstairs, run the bath, and climb in with the blade. Instead I lock all of that up in my throat with everything else. And I leave the courthouse, set to explode years later, like a bomb from an old war, forgotten, until it all surfaces at last.

* * *

Twenty years later I stand in my Brooklyn studio apartment and hold my phone in my hand, staring at it with dread. It is the night before my first novel’s publication in the fall of 2001, and my mother is about to travel to New York for my launch at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. If I don’t make the call, I will read from the novel in front of her, a novel about surviving sexual abuse and pedophilia, inspired by events from my childhood—these autobiographical events, events I have never described for her—and she will find out the next evening in a crowded room full of strangers. And she will never forgive me if I do. So now is the time.

I could tell you I remember the phone call I made, what I said, what she said, but I’d be lying. I call. The borders around this conversation are like something hot was set down on the rest of the memory and it burned. I remember she was shocked, and she didn’t understand why I’d never told her. I didn’t either, but I do now.

Our family had passed through a season of hell, and this was what I’d done to survive it. I know at last: I never told her about this because I was sure I was protecting her. It wasn’t that I was ashamed of it, exactly. I knew it would grieve her. Another disaster. I was her other hand; she needed me. I couldn’t be broken too. And so I had hidden myself inside a lesser disaster to survive this one. Hidden myself altogether. My mother, day after day, going to work inside the death of the dream my father had had all those years ago, returning to us—her three children, the man she’d loved, now hurt and wanting to die—she needed me.

The novel I give her the next day details the secrets of the abuse and all that it brought. The story of my father’s accident, his despair, his death and how I survived that—that is not in the book, though I tried. “No one will believe this many bad things happened to one person,” my first agent had said, and I had cut it from the draft, inventing other apparently more believable destructions. Leaving it out was a way of surviving it all even all these years later. Writing the novel had told me only one of them was bearable, even though I knew I had survived both.

In the audience, as I finish reading from this novel, the world I hid from her now in these sentences, I find my mother’s eyes. She is smiling. I can tell it is hard for her but she is proud of me. Prouder than she’s ever been.

This is how we got each other through.

16 Minetta Lane

By Dylan Landis

The wives of my father’s friends do not iron shirts.

“I’m sure they don’t wash floors either,” my mother says evenly. She talks to me but also through me. We are alone in the elevator of our New York apartment building, going down to the basement, where a woman named Flossie is going to teach my mother, for two dollars, how to iron a man’s shirt.

My mother tells me the wives have degrees in psychology or in social work, and they see patients, like my father does in our living room.

“Let’s just say I’m conscious of it,” my mother says, and we step out into a vast gray complication of corridors.

It’s 1964 and I am eight years old. My public school is so strict that girls can’t wear pants, even in a blizzard. My father is writing his psychology thesis, “Ego Boundaries,” which I half believe is the name of some fourth, shadowy person who lives in our apartment. My father teases me that when I grow up, I will get my PhD and take over his practice, and I believe that too.

He doesn’t tell my mother that she will get her PhD.

My mother is a housewife.

We walk down a broad hallway with padlocked doors. The super’s red-haired daughter, Silda, gets to live down here. We roller-skate on the velvety floors and spy on Otto, the porter, who has a number on his arm and sleeps in a storage room behind towers of old newspapers.

The laundry room smells deliciously of wet wool, and it rumbles from the dryers. My mother says hello and how are you to Flossie in a bright voice, and Flossie looks up. She gives my mother the exact same half smile I see her give everyone who talks to her. She has deep folds in her face, and she is dark as a plum and delicate as a bird. Her iron looks heavy. It thumps on the board and the sound is a slow heartbeat that goes on all day.

The wives in our building pay her twenty-five cents a shirt.

I tug wet clothes from our washer. My mother selects a shirt, takes it to Flossie, and hands her money that disappears into a smock the color of clay. Then Flossie wedges the shirt onto the nose of the board.

My father wears a dress shirt every day. If my mother stops giving the shirts to Flossie, we could save five dollars a month.

I pull out rack after screeching metal rack from the wall till I find one that’s not full of someone else’s clothes hanging stiff and dry over the rods. As I drape my father’s socks and undershirts, I watch the lesson: Flossie ironing, then my mother ironing, then my mother listening to Flossie with her head tipped.

She is so beautiful, my mother. She has distant blue eyes and cheekbones like butter knives. Her chin is like one of my grandmother’s porcelain teacups. Once a week she sits for a portrait because an artist in our building, a woman she likes, asked her to model; and I see her slipping out of a cage, those hours, and talking about books and sipping tea with the artist, and watching the Hudson glitter.

Beneath the racks, behind the wall, are gas burners—rows and rows of beautiful orange-blue flames, kept under tight control. Otherwise they would rise up and lick the clothes.

Dryers cost a quarter. The racks are free.

My mother comes over with the shirt on a wire hanger.

“She’s an excellent teacher,” she says, and calls back to Flossie, “You’re an excellent teacher.” Then she says, “I’ve got my work cut out for me.”

* * *

A few weeks later my father does something startling, right in our living room. He asks my mother to dance.

It’s after dinner, and dark out, though for us it’s never daylight because our living room and kitchen are on the air shaft, low down, and my bedroom faces a brick wall.

My mother and I clear the table. My father, who usually goes straight to his desk, picks out a record album: The Boy Friend. Records are what we do for fun. We don’t have a TV. But we do have this record player made of thick, shiny plastic the color of eggplant. I am not allowed to touch it.

My father lifts the arm over the record and sets the diamond needle down. The overture starts, horns so effusive and cheery I know they’re lying. But my parents pretend this is what happiness sounds like.

My father settles on the sofa, unfolding elbows and knees like a praying mantis. My mother opens a book at the other end and tucks her toes under his leg.

“Dance for us, Yum,” my father says.

My mother dances?

Ladies start singing now, voices so chipper I want to slap them.

My mother smiles, shakes her head, and keeps reading. The book cover says The Golden Bowl. “Come on, Yum,” my father says encouragingly. “Dance.”

“I’m not a dancer,” says my mother.

But she stands.

Julie Andrews sings now that every girl needs a boy friend—that we would gladly die for him, which alarms me; it feels fake, like everything else on this record, and also familiar. My mother moves in a new way, at fir

st as if she’s testing the air for doneness, and then tangoing her way toward the wall-to-wall bookshelves with a boy friend we cannot see, on a stage that isn’t there. She swivels. She bites her lip. “Wow,” my father says, but she ignores him. She stalks, points one toe, hikes up her skirt, and pushes her bosom out.

Then the song ends and she sits as if she’d just walked into the room, retucks her toes, and opens The Golden Bowl to her bookmark.

“Yum!” my father cries, applauding. “Where’d you learn to do that?”

But he isn’t exactly asking, and my mother doesn’t exactly answer.

“Oh, I just make it up as I go,” she says.

* * *

Questions I don’t ask my mother that night:

Why don’t you dance every day?

Why not take your husband’s hand and pull him into the dance?

Why not take your daughter’s hand and pull her into the dance?

Where does the dancing mother go when she’s not here? Where has she been all our lives?

* * *

The dancing mother goes into hiding, but three years later, on a spring Saturday, when I am eleven, my father and I blunder into the place where she once lived.

I don’t think my mother meant us to see it.

We take the IRT to Fourteenth Street and stroll. My parents love strolling. My father’s dream is to stroll in Edinburgh again, and my mother’s dream is to stroll in Paris. We go downtown on Sixth Avenue and my parents hold hands. My father sings a song he learned in the navy—Dirty Lil, Dirty Lil lives on top of Garbage Hill. It makes me feel bad. Does he think she wants to live up there, having sailors tease her?

Suddenly women are shouting from high up, and balled-up bits of paper are scattered on the sidewalk like fat, chewed-up pearls, and I want to open one, because they seem to have dropped from a distant world.

“This is not right,” my father says grimly.

I always feel I’m dreaming when I walk by the ladies’ house of detention. It’s tall, with columns of dark windows, and it’s a prison, yet ladies are calling out from the inside, and I don’t understand what they’re shouting. Plus, if they are locked up and out of reach, how can they drop these wadded papers?

What are they trying to say?

We walk downtown some more, on narrow streets. Finally I ask, “Why do they drop those paper balls?”

My mother sighs. “They write down their names and phone numbers on those slips,” she says. “They’re shouting for people to call their husbands and children, and give them messages.”

“Like what messages?’ ” I’m thrilled. These little white balls are like light from stars that died long ago.

“ ‘I love you,’ ” my mother says brightly. “What else?”

We are deep in the West Village now. My father strolls us into a right turn, back toward Sixth, and my mother stops so abruptly I step on her heel.

If she feels it I can’t tell.

We’re on the corner of a street with a name you could sing: Minetta Lane, and my mother is looking at the first pink building I have ever seen.

I love it immediately. It is the Barbie DreamHouse I am not allowed to have. The windows have white shutters, and the house has a wrought iron gate. Behind the gate is a little foyer, or passageway, and a black hanging lantern that melts colors onto the walls.

“Oh,” my mother says, as if the air just got socked out of her. My father looks at her patiently. He likes to keep moving.

“I used to live here,” my mother says. She sounds amazed.

“It’s a sweet place, Yum,” my father says, and looks at his watch. “Aren’t you girls hungry?”

The hunger I feel is so unreasonable I can’t parse it, even to myself. But I want to be the daughter of this mother, the one who lives in a pink building, the one who dances.

My mother is lost in thought. I watch her. She searches the building with her gaze, looks dreamily through the gate, and then something slips. The muscles around her mouth soften slightly, so that I wonder if she holds her face in a pleasant posture for us much of the time.

It’s not a good feeling. I look over at my father, but he is just waiting, amiably watching my mother look at the house, then turning his attention to the Village street scene.

I hold the locked iron gate with both hands and try to will myself inside.

“I scream, you scream,” my father says. “We all scream . . .”

“How could you leave?” I ask.

My mother touches one of my hands. It stays tight around the iron bar. “The apartment was small and dark,” she says gently. “It faced the courtyard. It was nothing special.”

But she is wrong. The apartment has sun, and cats, and hanging plants. It has pink walls, like a stage set where the mother can dance. It has a vase of daisies. It has a table set for two.

“I promise you,” she says. “The inside was nothing like the outside.”

* * *

I’m fourteen in 1970 when we live in a suburb of New York called Larchmont. We own a house, barely. My mother still irons my father’s shirts. She puts them in the vegetable crisper to keep them wet till she can get to them. She has long since taught me Flossie’s art—cuff, cuff, collar, yoke, sleeve, sleeve. We make hospital corners, we mend hems and darn socks and scour rings off tubs. I’m expected to bleach the whites and fold my father’s undershorts out of the dryer, which disgusts me, but there is no getting out of it.

My mother’s oil portrait now hangs between my bedroom and my parents’. It captures her perfectly—the faraway blue gaze, a sadness so faint it’s really not there, bone structure so elegant you want to trace it with a finger. I need to own this painting, and plan to steal it someday.

I’m lounging on the guest bed in my mother’s messy study, the room where she types out bills for my father’s patients, when she mentions for the first time an artist she once knew. His name was Bill Rivers.

Bill is a man’s name. She’s only ever talked about my father and, just twice, a man she was married to briefly. All she’s said about him was that he killed her darling bulldog, Chiefie, by leaving him in a hot car.

I sit up.

“His name was Haywood, but everyone called him Bill.” She peers at my father’s handwriting, then releases a clatter from her red Selectric. “This was long before you were born,” she says, and swivels in her chair to face me.

“We were just friends,” she says. “I didn’t understand how good an artist he was, but I knew I liked being with him, and I liked being around the artists he spent time with. Those were some big names. He would take me to a bar in the East Village where painters and writers hung out. And Dylan . . . they thought I was interesting. I had wit in those days.”

“Gee,” I say. I’m afraid to talk because of the soap bubble shimmering around us.

She sighs. “It was a rapier wit. A group of us would be drinking and talking, painters and sometimes writers, and I was always the one with the line of sarcastic repartee that made everybody laugh.”

I’m so riveted I nod, nod, nod till I’m rocking.

“They loved having me there,” she says. “And I loved being there with them.”

This is not the woman who married my father and raised me.

“Bill and I had pet names for each other,” she says. “I called him Country Boy, because he came from a very tiny town in North Carolina.”

She begins to rub her legs repetitively through her pants without seeming to realize it. Her palms go ceaselessly up and down her thighs, up and down, up and down.

It’s embarrassing. I look at my own hands.

What did he call you? I ask.

“City Girl, of course.”

Pet names are a big deal to my mother. She gave my father one. He gave her one. She has a bunch of ridiculous ones for me, like Winning Ways, which sounds like the name of a racehorse to me, and—it’s hard to even say aloud—Pussy. So did she go out with this Bill Rivers person?

I’m about to ask another question when my mother swivels back to her desk and draws an explosive burst from the Selectric.

* * *

Partly by cheating in French and math, I finish tenth grade. It’s early July 1972, the summer of Watergate, and I’m flush, because I’ve inherited my friend J’s part-time job sorting transistors in a TV repair shop. J, who is fifteen, had an affair with the thirty-six-year-old married boss, so I’d been wary, but apparently this was not a requirement.

One day after the shop closes I come home and glimpse my mother locked in grievous conflict with the family checkbook at the dining table. She’ll sit like that, arching her back to stretch, for two or three days.

“Dylan, I need you to pick up dinner,” she says.

Too late. I’ve bolted upstairs.

We seem to have more money now. For one thing, she sends the shirts out. For another, last summer my father bought an Alfa Romeo convertible. He doesn’t trust me to drive it, and then it gets stolen. This seems like justice to me. Also, we have a gardener every week, which is major, because when we moved here two years ago, guess who mowed and raked.

“I’m going out,” I yell down, because I am one of those teenagers now. But the truth is that the sight of her chained to that chair—chaining herself to that chair—makes me angry.

It’s a monster, this checkbook. My father set it up—a binder whose spreadsheets have the wingspan of a yardstick. Lots of categories run across the top in my mother’s tiny, pretty script, and every category needs to be filled in for every check.

I would rather die.

My mother appears in the door of my room. It’s painted rose because she rolled up her sleeves and painted it with me, and it’s cloudy with cigarette smoke because I don’t obey my parents’ rules anymore. They don’t beat me and they won’t throw me out, and you can’t yell me into submission.

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About