- Home

- Michele Filgate

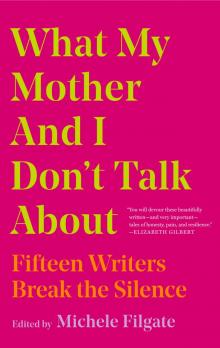

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About Read online

Praise for What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About

Most Anticipated Reads of 2019 Selection by *Publishers Weekly* *BuzzFeed* *The Rumpus* *Lit Hub* *The Week*

“A fascinating set of reflections on what it is like to be a son or daughter . . . . The range of stories and styles represented in this collection makes for rich and rewarding reading.”

—Publishers Weekly

“These are the hardest stories in the world to tell, but they are told with absolute grace. You will devour these beautifully written—and very important—tales of honesty, pain, and resilience.”

—Elizabeth Gilbert, New York Times bestselling author of Eat Pray Love

“By turns raw, tender, bold, and wise, the essays in this anthology explore writers’ relationships with their mothers. Kudos to Michele Filgate for this riveting contribution to a vital conversation.”

—Claire Messud, bestselling author of The Burning Girl

“Fifteen literary luminaries, including Filgate herself, probe how silence is never even remotely golden until it is mined for the haunting truths that lie within our most primal relationships—with our mothers. Unsettling, brave, sometimes hilarious, and sometimes scorching enough to wreck your heart, these essays about love, or the terrifying lack of it, don’t just smash the silence; they let the light in, bearing witness with grace, understanding, and writing so gorgeous you’ll be memorizing lines.”

—Caroline Leavitt, New York Times bestselling author of Is This Tomorrow and Pictures of You

“This collection of storytelling constellated around mothers and silence will break your heart and then gently give it back to you stitched together with what we carry in our bodies our whole lives.”

—Lidia Yuknavitch, national bestselling author of The Misfit’s Manifesto

“This is a rare collection that has the power to break silences. I am in awe of the talent Filgate has assembled here; each of these fifteen heavyweight writers offer a truly profound argument for why words matter, and why unspoken words may matter even more.”

—Garrard Conley, New York Times bestselling author of Boy Erased

“Who better to discuss one of our greatest shared surrealities—that we are all, once and forever, for better or worse, someone’s child—than this murderer’s row of writers? The mothers in this collection are terrible, wonderful, flawed, human, tragic, triumphant, complex, simple, baffling, supportive, deranged, heartbreaking, and heartbroken. Sometimes all at once. I’ll be thinking about this book, and stewing over it, and teaching from it, for a long time.”

—Rebecca Makkai, author of The Great Believers

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

Contents

Epigraph

Introduction

What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About

By Michele Filgate

My Mother’s (Gate) Keeper

By Cathi Hanauer

Thesmophoria

By Melissa Febos

Xanadu

By Alexander Chee

16 Minetta Lane

By Dylan Landis

Fifteen

By Bernice L. McFadden

Nothing Left Unsaid

By Julianna Baggott

The Same Story About My Mom

By Lynn Steger Strong

While These Things / Feel American to Me

By Kiese Laymon

Mother Tongue

By Carmen Maria Machado

Are You Listening?

By André Aciman

Brother, Can You Spare Some Change?

By Sari Botton

Her Body / My Body

By Nayomi Munaweera

All About My Mother

By Brandon Taylor

I Met Fear on the Hill

By Leslie Jamison

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

About the Editor

Permissions

For Mimo and Nana

Because it is a thousand pities never to say what one feels . . .

—Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway

Introduction

by Michele Filgate

On the first cold day of November, when it was so frigid that I finally needed to accept the fact that it was time to take my winter coat out of the closet, I had a craving for something warm and savory. I stopped at the local butcher in my neighborhood in Brooklyn and bought a half pound of bacon and two and a half pounds of chuck beef.

At home, I washed and chopped the mushrooms, removing their stems and feeling some sense of satisfaction as the dirt swirled down the drain. I put on Christmas music, though it wasn’t even close to Thanksgiving, and my tiny apartment expanded with a comforting smell: onions, carrots, garlic, and bacon fat simmering on the stove.

Cooking Ina Garten’s beef bourguignon is a way I feel close to my mother. Stirring the fragrant stew, I’m back in my childhood kitchen, where my mother would spend a good chunk of her time when she wasn’t at work. Around the holiday season, she’d bake poppy seed cookies with raspberry jam in the middle, or peanut butter blossoms, and I’d help her with the dough.

As I’m making the meal, I feel my mother’s presence in the room. I can’t cook without thinking of her, because the kitchen is where she feels most at home. Adding the beef stock and fresh thyme, I’m reassured by the simple act of creation. If you use the right ingredients and follow the directions, something emerges that pleases your palate. Still, by the end of the night, despite my full belly I’m left with a gnawing pain in my stomach.

My mother and I don’t speak that often. Making a recipe is a contract with myself that I can execute easily. Talking to my mother isn’t as simple, nor was writing my essay in this book.

It took me twelve years to write the essay that led to this anthology. When I first started writing “What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About,” I was an undergraduate at the University of New Hampshire, wowed by Jo Ann Beard’s influential essay collection The Boys of My Youth. Reading that book was the first instance that showed me what a personal essay can really be: a place where a writer can lay claim for control over their own story. At the time, I was full of anger toward my abusive stepfather, haunted by memories that were all too recent. He loomed so large in my house that I wanted to disappear until, finally, I did.

What I didn’t realize at the time was that this essay wasn’t really about my stepfather. The reality was far more complicated and difficult to face. The core truths behind my essay took years to confront and articulate. What I wanted (and needed) to write about was my fractured relationship with my mother.

Longreads published my essay in October 2017, right after the Weinstein story broke and the #MeToo movement took off. It was the perfect time to break my silence, but the morning it was published, I woke up early at a friend’s house in Sausalito, unable to sleep, rattled by how it felt to release such a vulnerable piece of writing into the world. The sun was just rising as I sat outside and opened my laptop. The air was thick with smoke from nearby wildfires, and ash rained down on my keyboard. It felt like the whole world was burning. It felt like I had set fire to my own life. To live with the pain of my strained relationship with my mother is one thing. To immortalize it in words is a whole o

ther level.

There’s something deeply lonely about confessing your truth. The thing was, I wasn’t truly alone. For even a brief instant of time, every single human being has a mother. That mother-and-child connection is a complicated one. Yet we live in a society where we have holidays that assume a happy relationship. Every year when Mother’s Day rolls around, I brace myself for the onslaught of Facebook posts paying tribute to the strong, loving women who shaped their offspring. I’m always happy to see mothers celebrated, but there’s a part of me that finds it painful too. There is a huge swath of people who are reminded on this day of what is lacking in their lives—for some, it’s the intense grief that comes with losing a mother too soon or never even knowing her. For others, it’s the realization that their mother, although alive, doesn’t know how to mother them.

Mothers are idealized as protectors: a person who is caring and giving and who builds a person up rather than knocking them down. But very few of us can say that our mothers check all of these boxes. In many ways, a mother is set up to fail. “There is a gaping hole perhaps for all of us, where our mother does not match up with ‘mother’ as we believe it’s meant to mean and all it’s meant to give us,” Lynn Steger Strong writes in this book.

That gap can be a normal and necessary experience of reality as we grow—it can also leave a lasting effect. Just as every human being has a mother, we all share the instinct to avoid pain at all costs. We try to bury it deep inside of us until we can no longer feel it, until we forget that it exists. This is how we survive. But it’s not the only way.

There’s a relief in breaking the silence. This is also how we grow. Acknowledging what we couldn’t say for so long, for whatever reason, is one way to heal our relationships with others and, perhaps most important, with ourselves. But doing this as a community is much easier than standing alone on a stage.

While some of the fourteen writers in this book are estranged from their mothers, others are extremely close. Leslie Jamison writes: “To talk about her love for me, or mine for her, would feel almost tautological; she has always defined my notion of what love is.” Leslie attempts to understand who her mother was before she became her mom by reading the unpublished novel written by her mother’s ex-husband. In Cathi Hanauer’s hilarious piece, she finally gets a chance to have a conversation with her mother that isn’t interrupted by her domineering (but lovable) father. Dylan Landis wonders if the friendship between her mother and the painter Haywood Bill Rivers ran deeper than she revealed. André Aciman writes about what it was like to have a deaf mother. Melissa Febos uses mythology as a lens to look at her close-knit relationship with her psychotherapist mother. And Julianna Baggott talks about having a mom who tells her everything. Sari Botton writes about her mother becoming something of a “class traitor” after her economic status changed, and the ways in which giving and receiving became complicated between them.

There’s a solid river of deep pain that runs throughout this book too. Brandon Taylor writes with astonishing tenderness about a mother who verbally and physically abused him. Nayomi Munaweera shares what it’s like to grow up in a chaotic household colored by immigration, mental illness, and domestic abuse. Carmen Maria Machado examines her ambivalence about parenthood being linked to her estranged relationship with her mother. Alexander Chee examines the mistaken responsibility he felt to shield his mother from the sexual abuse he received as a child. Kiese Laymon tells his mother why he wrote his memoir for her: “I know, after finishing this project, the problem in this country is not that we fail to ‘get along’ with people, parties, and politics with which we disagree. The problem is that we are horrific at justly loving the people, places, and politics we purport to love. I wrote Heavy to you because I wanted us to get better at love.” And Bernice L. McFadden writes about how false accusations can linger within families for decades.

My hope for this book is that it will serve as a beacon for anyone who has ever felt incapable of speaking their truth or their mother’s truth. The more we face what we can’t or won’t or don’t know, the more we understand one another.

I long for the mother I had before she met my stepfather, but also the mother she still was even after she married him. Sometimes I imagine what it would be like to give this book to my mother. To present it to her as a precious gift over a meal that I’ve cooked for her. To say: Here is everything that keeps us from really talking. Here is my heart. Here are my words. I wrote this for you.

What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About

By Michele Filgate

Lacuna: an unfilled space or interval, a gap.

Our mothers are our first homes, and that’s why we’re always trying to return to them. To know what it was like to have one place where we belonged. Where we fit.

My mother is hard to know. Or rather, I know her and don’t know her at the same time. I can imagine her long, grayish-brown hair that she refuses to chop off, the vodka and ice in her hand. But if I try to conjure her face, I’m met instead by her laugh, a fake laugh, the kind of laugh that is trying to prove something, a forced happiness.

Several times a week, she posts tempting photos of food on her Facebook page. Achiote pork tacos with pickled red onions, strips of beef jerky just out of the smoker, slabs of steak that she serves with steamed vegetables. These are the meals of my childhood—sometimes ambitious and sometimes practical. But these meals, for me, call to mind my stepfather: the red of his face, the red of the blood pooled on the plate. He uses a dish towel to wipe the sweat from his cheeks; his work boots are coated in sawdust. His words puncture me, tines of a fork stuck in a half-deflated balloon.

You are the one causing problems in my marriage, he says. You fucking bitch, he says. I’ll slam you, he says. And I’m afraid he will; I’m afraid he’ll press himself on top of me on my bed until the mattress opens up and swallows me whole. Now, my mother saves all of her cooking skills for her husband. Now, she serves him food at their farmhouse in the country and their condo in the city. Now, my mother no longer cooks for me.

* * *

My teenage bedroom is covered in centerfolds from Teen Beat and faded ink-jet printouts of Leonardo DiCaprio and Jakob Dylan. Dog-fur tumbleweeds float around when a breeze comes through my front window. No matter how much my mother vacuums, they multiply.

My desk is covered in a mess of textbooks and half-written letters and uncapped pens and dried-up highlighters and pencils sharpened to slivers. I write sitting on the hardwood floor, my back pressed against the hard red knobs of my dresser. It isn’t comfortable, but something about the constant pressure grounds me.

I write terrible poems that I think, in a moment of teenage vanity, are quite brilliant. Poems about heartbreak and being misunderstood and being inspired. I print them out on paper with a sunset beach scene in the background and name the collection Summer’s Snow.

While I write, my stepfather sits at his desk that’s right outside my bedroom. He’s working on his laptop, but every time his chair squeaks or he makes any kind of movement, fear rises up from my stomach to the back of my throat. I keep my door closed, but that’s useless, since I’m not allowed to lock it.

Shortly after my stepfather married my mother, he made a simple jewelry box for me that sits on top of my dresser. The wood is smooth and glossy. No nicks or grooves in the surface. I keep broken necklaces and gaudy bracelets in it. Things I want to forget.

Like those baubles in the box, I can play with existing and not existing inside my bedroom; my room is a place to be myself and not myself. I disappear into books like they are black holes. When I can’t focus, I lie for hours on my bottom bunk bed, waiting for my boyfriend to call and save me from my thoughts. Save me from my mother’s husband. The phone doesn’t ring. The silence cuts me. I grow moodier. I shrink inside of myself, stacking sadness on top of anxiety on top of daydreaming.

* * *

“What are the two things that make the world go ’round?” My stepfather is asking me a question

he always asks. We are in his woodworking shop in the basement, and he’s wearing his boots and an old pair of jeans with a threadbare T-shirt. He smells like whiskey.

I know what the answer is. I know it, but I do not want to say it. He is staring at me expectantly, his skin crinkled around half-shut eyes, his boozy breath hot on my face.

“Sex and money,” I grumble. The words feel like hot coals in my mouth, heavy and shame-ridden.

“That’s right,” he says. “Now, if you’re extra, extra nice to me, maybe I can get you into that school you want to go to.”

He knows my dream is to go to SUNY Purchase for acting. When I am on the stage, I am transformed and transported into a life that isn’t my own. I am someone with even bigger problems, but problems that might be resolved by the end of an evening.

I want to leave the basement. But I can’t just walk away from him. I’m not allowed to do that.

The exposed light bulb makes me feel like a character in a noir film. The air is colder, heavier down here. I think back to a year before, when he parked his truck in front of the ocean and put his hand on my inner thigh, testing me, seeing how far he could go. I insisted he drive me home. He wouldn’t, for at least a long, excruciating half hour. When I told my mom, she didn’t believe me.

Now he is up against me, arms coiled around my back. The tines of the fork return, this time letting all the air out. He talks softly in my ear.

“This is just between you and me. Not your mother. Understand?”

I don’t understand. He pinches my ass. He is hugging me in a way that stepfathers should not hug their stepdaughters. His hands are worms, my body dirt.

I break free from him and run upstairs. Mom is in the kitchen. She’s always in the kitchen. “Your husband grabbed my butt,” I spit out. She quietly sets down the wooden spoon she is using to stir and goes downstairs. The spoon is stained red with spaghetti sauce.

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About