- Home

- Michele Filgate

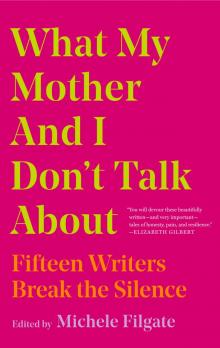

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About Page 6

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About Read online

Page 6

Back home, I sorted through the pictures, deleting the doubles and smiling at our happy faces. When I got to that video and played it, I saw an image of her sandaled foot—wide and strong like my own—on the gritty floor of the rented Fiat. Our voices, recorded with perfect clarity, commented on the scenery. I realized that she had been holding the phone’s camera upside down the whole time. I snorted and kept watching her shifting foot as we remarked on a passing bus. Then, I closed my eyes and listened to our conversation moving eagerly from subject to subject, our gasps as mopeds sped by us on hairpin turns, and our laughter ringing on and on.

Xanadu

By Alexander Chee

We were allowed to testify in a room by ourselves, taped testimony, because we were minors. As I sat in the waiting room with one of the other boys, a friend of mine, he said, with a shrug, “I let him give me a blow job.” He leaned back after he said it, and then held out his hands. “I mean, I’m okay. It didn’t hurt me.”

I nodded and wondered if I felt the same way.

We were fifteen, almost sixteen. We had been in the same boys choir for years and had both just left, our voices having changed. I had seen the boys from the choir have to change schools once the details came out in the press. I already knew that people treated us, the victims, as if we were also criminals. I had discovered the way everyone has an opinion when they discover you were sexually abused. Everyone seems to think immediately of how they’d have handled it better, and they expect you to answer their questions to confirm this. To come forward, especially if you’re a boy, is to be told you failed, implicitly, or even explicitly.

I had agreed to testify but had not identified myself as a victim. The director faced fifteen counts.

I tried out my friend’s tone. Even his statement.

It wasn’t that bad. I knew I was lying to myself, and he was too. I wasn’t going to say this lie, not yet. But I could leave myself out.

I would think of this a year later when I had to convince this friend not to kill himself by telling him he wasn’t gay.

I can tell you he was my friend, but there isn’t really language, a single word, for what and who we were to each other. We were also having a sexual relationship at the time we were about to testify. One that had begun in front of the director, on a camping trip, done to amuse him. Months after that, the relationship began, as if we needed the time to pass. We played Dungeons and Dragons together—he was always the Paladin; I was always a Magic-User. I wasn’t in love with him, but I loved him—I still do. I didn’t know how to call what we had found a name. Sometimes I’ve referred to him as my first boyfriend, but we didn’t hold hands, didn’t go to prom together as dates—when we did go, we were both with girls. What we had begun one day without any words felt more real to me in those moments. We never called it anything. One or the other of us would make a plan to hang out, and it could mean anything. I wonder sometimes if we were consoling each other, but I don’t know because we almost never spoke to each other about what we did. His waiting-room admission to me about what had happened that day didn’t shock me; I had seen what he was talking about, in front of me.

At the time it had happened, my friends and I in the choir had the habit of drawing elaborate forts, full of soldiers, weapons, planes, submarines—an impossible structure. The choir was like this, it seems to me now. Or I was. Full of secrets too complicated to explain. But maybe a map could say it all. This is an attempt at one.

* * *

I had joined the choir at age eleven. The director’s approaches to me began at age twelve and had been pitched at both my pride in myself, as a precocious child, and my shame in myself as biracial, queer, a social pariah at my school. He fed my belief that I was talented, intellectually more mature than my peers, and emotionally more mature also, from the beginning. He praised my voice and sight-reading ability at my audition and chose me as a section leader, and then as a soloist. This meant rehearsals alone with him. I trusted him because he made me feel good, even superior, at a time when I felt abandoned by the world. And when I say this, I mean specifically that I was a Korean American biracial child in a town that didn’t seem to believe people of different ethnicities would even marry, much less have a child. On any given day I felt like a freak, too visible in the wrong way, which is the same as not being seen.

I had a three-octave voice as a soprano, with forceful top notes, and the ability also to blend that voice with those around me. As a sight reader, able to read the music and sing it decently through the first time around, I was valuable to the learning of the music, and soon I discovered that whatever racism afflicted my classmates, here I was welcomed as a leader. I became popular and won the affection of friends. At middle school, I was still cornered or excluded. But now at choir, friends surrounded me. I needed a place to belong more than I even knew then. But the director knew. And so he had acted to me as if only he could provide it. This is what I now know is called grooming the victim. This choir full of talented boys, many of them outcasts like me, many of them queer, was for a short time my paradise, because it was also a trap, for all of us. Made out of us.

On the surface it looked as if I was going to choir practice, but inside, each day I went, I was running away from home. To what felt like the only place in the world that would accept me and nurture me. As we sang for larger and larger audiences, their applause felt like a relief I could never have imagined.

* * *

The director’s crimes were revealed the same year we mourned my father, who died on a January day almost three years to the day after his accident—a period that was almost the entire time I was in the choir. At the time I speak of, I was my mother’s right hand and had become so immediately. The day the phone call came from the hospital telling us my father had been in a car accident, she left to be at his side, leaving us behind in the house with a family friend until more was known. I don’t remember that I was able to do anything but remain in the family room, across from the phone, waiting for her to call. In those first moments, between when the family friend taking care of us arrived and my mother left, I knew this was the moment my father had spoken of when he told me that if anything ever happened to him, I was to be the man in the family, and something in me changed accordingly.

When she called and the phone rang, it shot up into the air and flew toward me as if I had lifted it with my mind. The telekinesis I had longed for while reading comics, suddenly there, as if released by the crisis, just like in those stories. But if it was, I apparently locked it up right away. This never happened again.

When I picked the receiver up, it was my mother, speaking to me, barely able to say what she was saying, and I knew we were in a new world.

* * *

My father had been in a head-on collision, and his business partner, the driver, less seriously injured, died a few days later. My father was in a coma for three months. We went to the hospital to read to him in turns, our voices said to help him return to consciousness. I don’t recall the book, just the reversal, the man who used to tell me stories, now apparently listening to me from within this coma, as if I could guide him with one. What I could tell no one now as I sat by his bed, reading to him, was as huge as my life: I blamed myself for my father’s accident.

The previous fall, I had asked for permission to skip swim practice so I could go on a roller-skating trip with the Webelos. I was not an experienced skater but my favorite movie in the world then was Xanadu, and I wanted to skate around the rink and imagine myself singing along to the songs, covered in light like Olivia Newton-John—and secretly imagining I was her. But instead I fell off my skates that night and landed on my left arm. When I looked at it, it was crooked, like a branch on a tree. I let out a scream perhaps only a boy soprano could, one that stopped the music in the rink, and in my memory there is a spotlight on my arm, before I began my scream, at which point the other skaters stopped to look on in horror as the disco stops.

My mother, on her way to the rink, pulled over t

o let the ambulance pass by, wondering who had been hurt.

At the hospital, I recall the doctor setting my arm, saying the device he was inserting my fingers into was like a medieval torture device, something made for interrogations, now used to help separate the broken bones so they could be set properly. The old torture machine pulled my arm smooth. The arm was x-rayed, wrapped in a cast. Soon I was home, contrite, logy with pain medication. Over the next few days I learned that as I could no longer go to swim practice, my coach was furious. And we would not be going to Florida on vacation, as I would just get sand in my cast.

The night of my father’s accident, when his car slid in the snow and ran into the car in the other lane, I told myself we were to have been safely on a beach, and I never forgot it. I waited to be blamed. The cast was still on my arm, itchy and strange. But no one said anything to me.

Thirty-five years would go by before I would tell my mother this. I had finally realized my theory about it was a memory but one I wasn’t sure I should trust. The shock on her face was terrible to see, like she was watching me turn into something she never knew could exist. “We had to cancel the trip because of your father’s work,” she said. “Not because of your arm. We would never have done that.” I tried to see if I believed her. I knew at least she believed herself.

Had I made up the conversation I was sure I remembered, telling me the trip was off? It made sense that my arm alone wouldn’t have stopped us—it was an international, multimillion-dollar deal my father was working on, after all. He wouldn’t take a family vacation in the middle of it. This was the deal my father believed was his ship coming in. He had been taking me to see luxury cars, as he was going to buy one to treat himself. Or he drove them to us, picking us up at school for a test drive. One week he came to school in a Mercedes convertible, white with red leather interior. The next day, an Alfa Romeo. The next day, a Jaguar. He was so full of joy as he pushed the door open, his smile so bright. And then came that winter.

Years later classmates confessed they had thought we were rich, and all the cars were ours.

With distance I can see how, as unbearable as his injuries were to him—paralyzed down the left side of his body, the accident had drawn a rough line down his center—all his dreams were broken too. He’d been a martial artist since childhood, and his conditioning was such that he had survived this crash that had taken the life of the driver, less severely injured. He had trained his whole life to survive no matter what, and now he had, and he wanted to die.

He had been so strong all my life, this man who raced me in holding my breath underwater just months before, doing fifty, seventy-five yards without a breath. The man who had taken me into the basement to teach me to box, who made me study karate and tae kwon do after the kids at school had cornered me. The man who had thrown me into a wave for crying with fear at the ocean, and then taught me over the years to beat the riptide. “You need to be able to swim well enough that if the boat is going down, you can swim to shore,” he told us.

I did not know where the shore for this was.

I am twelve. My hero is my father and he is broken. And I believe I broke him, my own broken arm pushing him into the car. I believed it until four years ago.

* * *

Over the three years my father was convalescing from the injuries he would eventually die from, in the first year, after he woke from his coma, he lived at home, in a makeshift bedroom that was once our living room. He was angry and depressed, suicidal at times, and when I got home from school I would visit with him before attending to homework. A cousin from Korea was sent by our family there to live with us, to be his companion, an older man I liked all right, though he seemed fidgety. He watched K-dramas or played cards with my father, who had once been an excellent poker player, and dispelled some of the airless gloom of my father’s sadness and fury. We had fought for him to live and he did not want to live now, and it was hard not to feel we’d failed him. My mother taught me how to make several hamburger casseroles—American chop suey, which was really just elbow pasta in a tomato gravy; “Texas hash,” which was essentially the same but with rice; and a beef Stroganoff that was made by pouring sour cream and cream-of-mushroom soup onto ground beef, and which I often served on rice also. My mother now worked at the fisheries business; the deal he’d been working on fell apart without the men who had been at its center. She faced the difficulties of being a woman in a business dominated by men, and would come home at the end of the day, exhausted, to the man she had loved enough to marry and defy her family and culture. The stories she told, of the way her work alienated her from many of the women who had been her friends, of the way the men who worked with my father were being won over by her but had to be won over, came out at these times. I would listen, sometimes give her a back rub or a shoulder rub as she confided in me, and bring her a glass of scotch on the rocks. I was, am, a receptive ear, to many, and I learned it here.

I just never knew how to tell her what was happening when I was away from home.

I am known for speaking when everyone else is silent, of saying the thing everyone is thinking but no one will say. And so it is all the stranger to me that I won’t say this, won’t speak up about this, when I look back, until I remember, for me, it was like a secret paradise. The only pleasure I had besides food was singing. Until it was just another hell. A less terrible one.

A year passes, and my father’s sister convinces us she will care for him in her home. A doctor near her in Massachusetts has, she insists, the possibility of restoring him. We take the second cousin and my father there, and for a year, go back and forth to see him. A year after that, when we understand the doctor is really just experimenting on my father, and endangering him, we bring him back to Maine, this time to a facility near us in Falmouth.

The choir becomes bigger, more professional. I had been briefly proud of my leadership and popularity, but once the director had had what he wanted from me, these made me a threat to him. He accuses me of creating cliques with my Dungeons and Dragons games, and tries to isolate me socially. I’m still the section leader, but no more solos. My strange relationship with my friend is now the silent center of my life, the world between us, sex taken when we can find it. The terrible pain of the rest of life is erased in those moments. My memories of him are still another color from the rest, as if they were all lived in another dimension.

A favorite memory of summer is a week at his parents’ lake house. We sneak out to the lake at night, and make our way to swim, finding each other eventually in the liquid dark. However we met each other feels erased to me, or worth it somehow, for this. But I don’t tell him and so I don’t know how he feels. I wonder sometimes what would have happened if I’d said something there also.

The secrets hidden in me could fill that lake, but don’t. They leave with me.

* * *

Now I am fifteen. I move through my days like a kind robot, someone whose job is to bring a version of me around to attend to all of the things that need doing. But sometimes there are outbursts, storms of anger. In a fight with my brother, I try to get him to shut up, and when I can’t, I get on his chest with my knees. I can still see the startled fear in his eyes.

In my role as the cook, I am near the food, and so I eat. Bagels with cream cheese for breakfast, pepperoni pizza or a hamburger or cheeseburger for lunch, roast beef sandwiches with Muenster cheese, kielbasa and eggs, ham and melted cheddar. Food is our first experience of care, a child psychiatrist tells me, when I go. My mother has sent me because of my eating. I’ve gained weight. He asks if I feel unloved, and I don’t know how to answer that. I eat for the pleasure I feel, the annihilating pleasure of it. I eat because I’m too smart for my own good, too sensitive, too queer, too Asian, too sad, too loud, too quiet, too angry, too fat. I eat because I wanted to go roller-skating, to be surrounded by disco light, and it brought my world down to the ground and I won’t ever escape this way, but it feels like I do. As if I could chew my way out

of this hell.

When my voice finally changes, it feels like a replacement in my throat, a struggle, like something is dying. The high soprano notes I could sing, the way they illuminated me, my vocal chords like filaments, this all leaves, and it is hard not to feel like a darkness is left behind. It is at least the absence of that specific light. I can hear it still, can still feel the way the notes filled my head and throat like the air I would hold as I went underwater. The vibration of my body to the sounds I could make in my throat was simply a more vigorous way of being alive.

I won’t learn to sing with my adult voice for thirty years, when I fall in love with a man who has an adult voice as beautiful as any of the pop stars he covered in his high school band. We will go to karaoke in that distant future, so much so that my own voice will begin to respond as if I am going to rehearsals again. I still don’t feel it’s the same. It is as if I had a voice that left and another that arrived, and not a voice that changed.

When I give my testimony, that is the voice I use. The newcomer. I describe the trips, the way he would pick a favorite and train him and get him alone by giving him a solo. I don’t say I know because he did it to me. I don’t say he tried to make me feel special when it seemed like no one else would, or that the room of children, many of them gay, was my first queer community. I don’t say that I found my first boyfriend there, and that it let me feel connected to this world when nothing else did, and how so many of us were like that, chosen because we were so much alike—boys who needed someone to prop up our world, who would let him do what he did in exchange for that. Boys without fathers, or with broken ones. Boys with moms who were trying to save their homes. I say it happened to other people; I act like I’m just being cooperative. I don’t say that I wanted to die of the guilt, of feeling that I helped make all of this happen, and that it all happened because I was queer.

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About