- Home

- Michele Filgate

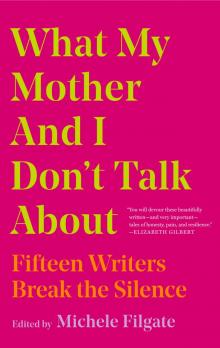

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About Page 4

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About Read online

Page 4

Well, listen. I cannot imagine losing a child, cannot imagine how anyone goes on. He can think whatever he wants about that. While I was contemplating all this, my mother said, “But you know, Cathi, you want to take on everything with him. And I think it’s better to let some things go. It’s like you’re always looking to correct him, or—you’re on him. Amy gets louder and more aggressive at times, but she also engages with him a lot about political things and other things, so they have a deep connection. With you, it’s just more antagonistic.”

Once more, fair—and helpful, in some ways. As the firstborn and the sister arguably most affected, back then, by his narcissism and authoritarianism, I don’t cut him much slack.

“When he goes on Facebook as you,” I said, “does that ever bug you?” He doesn’t have his own Facebook page, so he uses hers. There he comments on the threads of her “friends”—me, for example—sometimes with attempted humor, sometimes antagonism, for my own friends and readers (many of whom I don’t know) to see. I sign on and shake my head. Delete delete delete. “He doesn’t go on as me,” she said. “He always signs his initials.” Never mind that it’s her face and her name, or that sometimes he forgets the initials, or that few, if any, of those who see his comments understand that “LBH not BFH” at the end of the post means it’s him, not her. Once, I told her if she didn’t control him, I’d have to unfriend her. It worked for about a week.

I said, finally, “Were you ever scared of him? Did you ever have a fight where you felt like leaving?”

“I think a few times,” she said, as if she can’t quite recall. “It bothers me when he yells. But I never would have left. We have a life together. Whatever it was, it would get straightened out.” She paused. “And I don’t think he yells so much anymore.”

I laughed. If love is blind, love is also, apparently, deaf. My father is the same person he always was—at least for the fifty-five years I’ve known him. And so is my mother.

I thanked my lovely, sweet mother for her time and her honesty, and we hung up our phones.

* * *

So here is the end of my story—the epilogue, maybe. In 1953, my mother met the man of her dreams, and in 1957, they married. In a scoop-neck white dress, barely over nineteen years old, she pledged to have him and hold him, for better and for worse, ’til death did them part. In her diligent green eyes, and as the daughter of a gentle, loving man who believed that you accept what life deals you with a smile and a nod, she entered into a lifelong agreement where my father would provide for her and make the decisions, and she would accept them—and that’s what she’s done. In exchange, she’s gotten a faithful, loyal husband, one who screams and yells and loses his temper and humiliates her now and then, one who at times spanked and berated her children, but one who also provided for her and those children, enriched her life with culture, and relied on her as surely and heavily as she relied on him. Was he abusive, or just inflexible and empathy-challenged? Really, does it matter? A label is only that. And as Elie Wiesel said, the opposite of love is not hate, but indifference—and one thing you could never call my father was indifferent. He was there. Front and center, in your face, all the time. And through six decades, four children, six grandchildren, many dogs, many travels, my mother has been okay with that. She has stood by his side, putting him first.

The mystery of my mother is solved, then, and it’s this: There is no mystery—and in fact, it’s only my desire to make it otherwise that’s kept it from being downright banal. Like her own father, my mother deals with life’s frustrations and devastations mostly by waiting them out and not analyzing too much; by keeping busy, turning a blind eye if needed, helping the truly disadvantaged when she can, and not letting the shit get her down. Unlike me, she didn’t and doesn’t need answers for all of life’s questions; she made her bed at sixteen, and now, sixty-five years later, she still lies in it, sanguine and content. She is exactly what I see, and exactly what she wants to be; what she wants is, most of the time, just what she has, and the rest of the time she endures until things improve. As my father said to me recently when he saw me doing whatever I was doing, trying to open some can of worms, “She’s happy. Don’t make her think she’s not.”

He is right. And so I don’t anymore. After all, her story is her story: a love story, with her own happy ending.

And my story—about love, yes, but also about forgiveness—is mine.

Thesmophoria

By Melissa Febos

I. Kathodos

Steam seemed to rise from the sidewalks of Rome. It was July of 2015, the air thick with heat, cigarette smoke, and exhaust. I had been awake for almost twenty-four hours, three of which I had spent waiting at the airport for an available rental car. I had driven into the city amid bleating horns and the growl of mopeds that darted like wasps around cars. I parked in a questionable spot and wove through the crowded sidewalks until I found the address of my rental. In the tiny apartment, I pulled the curtains and crawled into the strange bed with its coarse white sheets. I posted a photo on Facebook of my shiny exhausted face—Italia!—and fell instantly asleep.

Three hours later, I woke to the ding of my phone. I had three text messages from my mother. Months previous, she had cleared her schedule of psychotherapy patients and purchased her ticket to Naples, where I would pick her up at the airport in four days. From there, we would drive to the tiny fishing town on the Sorrento Coast where her grandmother had been born, and where I had rented another apartment for a week.

You are in Italy??

My ticket is for next month!

Melly???

A spear of dread pierced through the fog of my jet lag, turning my stomach. Praying that I had not made such a colossal mistake, I frantically scrolled through our emails, scanning for dates. It was true. I had typed the wrong month in our initial correspondence about the trip. Weeks later, we had forwarded each other our ticket confirmations, which obviously neither of us had read closely. My head hummed with anxiety.

The panic I felt was more than my disappointment at the ruin of our shared vacation, to which I had so been looking forward. It was more than the sorrow I felt at what must have been her hours of panic while I slept, or her imminent disappointment. It was more than the fear that she would be angry with me. Who wouldn’t be angry with me? My mother’s anger never lasted.

* * *

Imagine a foundation as delicate and intricate as a honeycomb, a structure that could easily be crushed by the careless hand of error. No, imagine a structure that has weathered many blows, some more careless than others. The dread I felt did not rise from my thoughts but from my gut, from some corporeal logic that had kept meticulous track of every mistake before this one. That believed there was a finite number of times one could break someone’s heart before it hardened to you.

* * *

For the first year, it was just us two. My mother, who had been such a lonely child, wanted a daughter. Then she had me. It was the first story I understood to be mine. Melissa, which means “honey bee,” was the name of the priestesses of Demeter. Melissa, from meli, which means “honey,” like Melindia or Melinoia, those pseudonyms of Persephone. We all know the story: Hades, king of the underworld, falls in love with Persephone and kidnaps her. Demeter, her mother and the goddess of agriculture, goes mad with grief. During her relentless search for Persephone, the fields go fallow. Persuaded by Demeter and the pleadings of hungry people, Zeus commands Hades to return Persephone. Hades obeys but first convinces Persephone to eat four seeds of a pomegranate, thus condemning her to return to Hades for four months of every year—winter.

* * *

I don’t know how it feels to create a body with your own. Maybe I never will. I remember, though, how it felt to be a daughter of a daughter, the distance between our bodies first none, then some. She nursed me until I was nearly two years old, already speaking in full sentences. Then, she fed me bananas and kefir, whose tartness I still crave. She sang me to sleep against

her freckled chest. She read to me and cooked for me and carried me with her everywhere.

What a gift it was to be so loved. More so, to trust in my own safety. All children are built for this, but not all parents to meet it. She was. Not my first father, so she left him. First, we lived with her mother and then in a house full of women who had decided to live without men. One day on the shore, we found our sea captain strumming a guitar, my real father. From the day they met, he never knew one of us without the other. Today when I see him, the first or second thing he says to me is always, Ah! Just now, you looked exactly like your mother.

They both dote on the memory of me as a child. Fat and happy, always talking. You were so cute, they say. We had to watch you. You would have walked off with anyone.

When he was at sea, it was just us again. After my brother was born, it was me in whom she confided about how much harder it got to be left by him. Her tears smelled like sea mist, cool against my cheek. Like they had doted on me, I doted on my brother, our baby.

After my parents separated, they tried nesting—an arrangement where the children stay in the family home while the parents rotate in and out of it. The first time my father returned from sea and my mother slept in a room she rented across town, I missed her with a force so terrible it made me sick. My longing felt like a disintegration of self, or a distillation of self—everything concentrated into a single panicked obsession. My toys all drained of their pleasure. No story could rescue me. To protect my father, whose heart was also broken, I hid my despair. In secret, I called her on the telephone and whispered, Please come get me. I had never been apart from her. I hadn’t known that she was my home.

* * *

My birthday falls during the fourth month of the ancient Greek calendar, also the month of Persephone’s abduction, the month Demeter’s despair laid all the earth to waste. During it, the women of Athens celebrated Thesmophoria. The rites of this three-day fertility festival were a secret from men. They included the burying of sacrifices—often the bodies of slain pigs—and the retrieval of the previous year’s sacrifices, whose remains were offered on altars to the goddesses and then scattered in the fields with that year’s seeds.

When I got my first period at thirteen, my mother wanted to have a party. Just small, all women, she said. I want to celebrate you. It was already too late. I seethed with something greater than the advent of my own fertility, the hormones catapulting through my body, the fact of our severed family, the end of my child form, or the cataclysm of orgasms I masturbated to each night. These changes weren’t all bad. I had been taught by her to honor most of them. But there were things for which she hadn’t prepared me, for which she couldn’t have. The sum of it all was unspeakable. I would rather have died than celebrate it with her.

It is so painful to be loved sometimes. Intolerable, even. I had to refuse her.

* * *

The psychologists have a lot of explanations for this. The philosophers, too. I have read about separation and differentiation and individuation. It is a most ordinary disruption, they tell us, necessarily painful. Especially for mothers and daughters. The closer the mother and the daughter are, they say, the more violent the daughter’s work to free herself. Those explanations offer something, though I am not looking for permission, atomic explanation, or assurance that ours was a normal break. Not only, anyway. I am also interested in a different kind of understanding. For that, I need to retell our story.

I imagine a beloved. A lover with whom I spend twelve years of uninterrupted, undifferentiated intimacy. A love affair in which the burden of responsibility, of care, is solely upon me. I imagine, also, simultaneous responsibilities. In Demeter’s case, the earth’s fertility, the nourishment of all people, and the cycle of life and death. After twelve years, my beloved rejects me. She does not leave. She does not cease to depend on me—I still must clothe and feed her, ferry her through each day, attend to her health, and occasionally offer her comfort. Mostly, though, she becomes unwilling to accept my tenderness. She exiles me from her interior world almost entirely. She is furious. She is clearly in pain and possibly in danger. Every step I take toward her, she backs farther away.

Of course, this is a flawed analogy. I turn to it because we have so many narratives to make sense of romantic love, sexual love, marriage, but none that feel adequate to the heartbreak my mother must have felt. The only way that I can imagine it is through these known narratives, and the kinds of love I have known. The attachment styles that define our adult relationships are determined in that first relationship, aren’t they? I have felt more than a few times the shock of losing access to a lover; it doesn’t matter who leaves. It feels like a crime against nature. To continue to live in the presence of that body would be a kind of torture. It must have been, for her. It must have been how Demeter felt as she watched Persephone be carried away in that black chariot, the earth broken open to swallow her.

II. Nesteia

I had spent that Saturday at the library with Tracy. That was what I had told her. When I got in the car that evening, the sun was half-sunk behind the buildings in town. The spring afternoon’s warmth had turned cool, a breeze from the nearby harbor bringing the soft clang of a buoy’s bell. I slid into the passenger seat, buckled my seat belt, and waved goodbye to Tracy. She turned to walk home. My mother and I watched her retreat, the edge of her T-shirt rippling in the wind. Her back was so straight. She did walk a little bit like a robot, as Josh had observed as he groped in my underwear, breath hot against my neck. My mother’s focus shifted onto me.

You smell like sex, Melissa, she said. Her voice wasn’t angry or surprised or cruel, only tired. In it was a plea. Please, it said, just tell me the truth. I know it already. Let’s be in this together.

It was easy to present the shock of my humiliation as the shock of incredulity. I had done so before and we both knew it.

I’ve never had sex, I said. I believed this.

My mother eased into first gear and turned toward the parking lot exit. Sex isn’t just intercourse, she said. We drove home in silence.

I don’t know if we had a conversation about trust that night. We had had them so many times before, my mother trying to broker an understanding, to cast a single line across the distance between us. If trust was broken, my mother explained, it had to be rebuilt. But the sanctity of our trust held no currency with me, so broken trust came to mean the loss of certain freedoms. It didn’t work. She didn’t want to revoke my freedoms; she wanted me to come home to her. Probably I knew this. If she didn’t like the distance my lies created, then she would like even less my silence and sulks, my slammed bedroom door. Of course I won. We each had something the other wanted, but I alone had conviction.

How many times could she call me a liar, or believe me one? I was relentless in my refusal to acknowledge what we both knew. I slept over at friends’ homes where older brothers coaxed me into closets or found me in the kitchen at midnight with a glass of water. I went on drug deliveries with a friend’s mother who dealt them. I snuck boys into our home or met them behind the movies. Grown men groped me in backyards and basements, on docks and in doorways, and there was nothing she could do.

* * *

The Rape of Persephone is depicted by hundreds of artists, across hundreds of years. The word rape translates as a synonym for abduction. In most of them, Persephone writhes in the arms of Hades, torquing her soft body away from his muscled arms, his enormous bulging thighs. In Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s famous baroque sculpture, Hades’s fingers press into her thighs and waist, the white stone yielding so fleshlike. Her hands often push against his face and head, a motion that evokes the response of an actual rape victim. Some of these works resemble that other violation more than others. In Rembrandt’s Rape of Proserpine, as his chariot plunges through foaming water into darkness and the Oceanids cling to her satin skirts, Hades grasps Persephone’s leg around his pelvis, though her gown hides the rest.

My mother surely feared th

at I would be raped. It was a legitimate danger. In hindsight, I am surprised that it never happened. Perhaps because I feared it as much as she did. Or because I so often yielded to those who would have forced me.

It must have felt like an abduction to her, as if someone had stolen her daughter and replaced her with a maenad. I chose to leave her, to lie, to chase those places where men with muscled thighs might lay their hands on me, but I was still a child. Who, then, was my abductor? Can we call him Hades, the desire that filled me like smoke, that chased everything else out? I was frightened, yes, but I followed him. Perhaps that was the scariest part.

A convention of Spartan weddings widely adopted across Greece was for a groom to seize his writhing bride across his body and “abduct” her by chariot, in a seemingly perfect simulacrum of Persephone’s abduction.

* * *

We all know the allure of the reluctant lover. But what of our own heart’s division? My ambivalence tormented and compelled me. That eros an engine that hummed in me, propelled me away from our home into the darkness. I knew it was dangerous. I couldn’t tell the difference between my fear and desire—both thrilled my body, itself already a stranger. And daughters were supposed to leave their mothers, to grope through the dark for the bulging shapes of men, and then resist them. My mother must have anticipated this, must have hoped she would be spared.

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About