- Home

- Michele Filgate

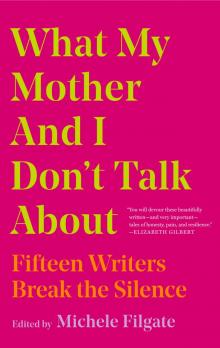

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About Page 3

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About Read online

Page 3

I could ask her now, along with this: Why didn’t she protest my father’s bad behavior, to her and her children and others? Or did she think there wasn’t actually a problem, and I was just oversensitive? (I know how my father would answer that.) When he’d smacked me, hard, in the face, in fourth grade because he overheard me use a word I didn’t even realize was forbidden; when he shoved my adolescent sister a little too hard and she plummeted—oops!—down the steps (She was fine! We had carpeting!); when he ridiculed me about my verbal SAT score (something he still does today, despite my longtime career as a novelist, editor, writer) . . . should I simply have ignored it and moved on, as my mother did?

My father had arbitrary rules for a girl who got good grades, didn’t get shit-face drunk, even helped run his medical office (he wouldn’t let me have any other job): I could go to the movies with my friends or boyfriend, but only to see films he deemed intellectual enough—so if a group of my fifteen-year-old friends was going to see, say, Halloween, or Jaws 2, I had to make them see The Deer Hunter instead, or I couldn’t go. Did my mother, my other guardian, agree with this parenting? He wasn’t beating me, starving me, kicking me out, but still: Why the hell didn’t she open her mouth? As a teenager I was too enraged to ask her calmly, though when I’d wail, “Why don’t you tell him to stop doing that?!” she wouldn’t, or couldn’t, or at any rate didn’t, say a word, no matter how I begged. Was she complicit? Afraid? As an adult, and with—finally!—direct access to her, I could get answers.

* * *

But access, I soon found, didn’t give me much more insight than I already had—at least not right away. Sometimes she simply didn’t respond when I asked about my father; other times she emailed back briefly, her answers short, unrevealing—at least to my mind. “I can’t control him,” she’d say, when I asked why she allowed him to throw a full, screaming tantrum on Thanksgiving because someone ate the last shrimp on the platter, even though there were more right in the kitchen. “It doesn’t matter what I tell him,” she would say, or, “If I ask him to stop, he just gets angry.” These all were and are true, but could you ignore such behavior from your husband? His grandchildren’s mouths dropped, before they went off to whisper and giggle (to be fair, they found him hilarious). Why didn’t she speak up? Give an ultimatum? Though what that might be, I couldn’t imagine.

What my email relationship with my mother did do was provide a way to talk to her that was fun.

Now if I asked a question about child-rearing or a recipe, she could answer it, all by herself. She’d tell me about a new kid she was tutoring, or about visiting a museum in the city with her oldest friend; going alone to New York was something she’d only begun doing in the past decade or so. She told me the history of her family. And we talked about books, now without anyone on the extension asking where the hell the letter opener was. My mother loves almost any novel, unless there’s “too much” smoking, drinking, swearing, or adultery. She began to follow the careers of my writer friends and to invite some of them, as she had me, to her book clubs. “I love your mother!” they would tell me, after busing to her house for egg salad and coffee with her peers, fresh-cut hydrangeas from her garden decorating the table. They liked my father, too, who picked them up at the bus stop, friendly and joking, turning on the charm and chivalry he calls up when he wants to. He reads books, too—and not just male writers, either. Among his favorites are Pride and Prejudice and Middlemarch. Four stars each.

But what my mother still didn’t do in our new email correspondence, at least not often or with depth, was self-analyze or discuss my father’s behavior—toward her, toward me, or in the world—in a way that made me understand what she thought about it. Sometimes she laughed or gently made fun of me for asking. (“Oh, Cathi, I don’t know!”) And eventually, now that I knew it was her choice not to talk about all this, or maybe just because I never got very far, I backed off—a little, at least. When I visited my parents, I tried to stay out of their relationship, though sometimes I failed. “Stop yelling at her!” I’d yell, when he exploded about the stupid fucking shrimp, or his pounds of cashews from Costco that someone dared help themselves to—and sometimes, now, he actually listened; it didn’t hurt that there were suddenly four mature granddaughters along with three adult daughters to jump on the Girl Power ship, his two mild-mannered grandsons, with their feminist mothers, cheering on their sisters and cousins. He was outnumbered. Sometimes I even felt sorry for him; another straight white man being #MeToo’d at his own dinner table. After all, if it weren’t for him, none of us would be here—in this room, or anywhere at all.

And overall, we were fine—fine!—in part thanks to him. We had good lives, weren’t estranged, got together a few times a year, a healthy, privileged family of thirteen or fourteen . . . not so bad, after fifty-five years. I had survived my childhood with him at its helm, and I still chose to engage and spend time with the guy, not just to access my mother, but because sometimes I enjoyed it and I knew he did, too. And because he wasn’t getting younger, and because, as always, he was generous in many ways: giving medical advice, taking my kids out to dinner or even on vacation, and, now, helping his grandchildren pay for college (as long as they went to schools he approved of: Cornell was ideal, because he’d gone there, but Brown was not; it was “pretentious”). He had always supported the positives in my life—particularly my work—as much as he’d blasted what he’d perceived as the negatives. He and my mother, the dark-haired, then gray-haired, then white-haired couple on the cruise to Helsinki or Venice or Juneau, handing out cards for my latest book and bragging about my husband’s newspaper column. I did not take that for granted.

The next day, though, he’d copy someone into a long personal email exchange between us (I’ve begged him not to), or comment disturbingly about some young girl’s attractiveness or lack thereof (ditto) . . . and there we were again. And my mother—my mother, whom this essay is supposed to be about (Do you see what happens here?)—my mother would go silent, almost as if she were condemning me, too. Was she? If so, then okay! But I wanted to hear it.

And so, to write this essay, I decided to find out, once and for all. My parents are eighty-two and eighty-one now; they’re healthy as horses, but you just never know when it’s your last chance to get answers to questions you’ve had your whole life. So I emailed my mother, saying I’m writing about the things we don’t talk about, and would she be willing to, well, talk to me about them. She said yes. We set up a time when my father would be at the hospital, where he still sees patients a few mornings a week. And we got on the phone.

My mother, it seems to me, has changed in the past twenty years, particularly the past ten. After the relentless busyness of so many decades of her life—the mothering, wife-ing, teaching, bookkeeping for my father’s practice—she’s had time to slow down and branch out. The women’s groups, the book groups, the board she’s sat on . . . at eighty-one, she’s no wallflower. I almost felt she was excited to talk to me; at any rate, I didn’t think she minded.

After some small talk, I cut to the chase. “When you two met,” I said, “did he have the temper he has now? If not, when did you first notice it?”

“He didn’t,” she said. “As his life got more complicated, he put a lot of strictures on how he wanted things to be. And when they weren’t that way, he got angry.” She paused. “But no, his temper didn’t come until much later, I think. I think. And that’s part of why we’ve stayed married all these years, Cathi—because I forget things quickly. I get very angry at him, and then I forget all about it. But I also didn’t, and still don’t, analyze marriage or relationships the way your generation does. We were a naïve age, I think.”

Fair enough, though great thinkers, from Gloria Steinem to Betty Friedan, Germaine Greer to the brilliant Vivian Gornick (almost exactly my mother’s age), also come from her generation. Still, three of those four didn’t have children—and yes, I do think that changed things back then: your worldview, your prior

ities, the power you had, if any, to be independent and therefore outspoken. “Do you agree he was your gatekeeper?” I asked. “That he shielded you from others? Me, your friends, some other family?”

“I think he definitely did, and still does, keep me from . . . like, the teachers at my school. The principal was always trying to organize after-school events, like meeting in a bar, or going out for dinner. And I never wanted to do those things”—here I couldn’t help noticing the shift, from what he wanted to what she wanted, seemingly one and the same—“first because I had four kids and a busy life—I kept the books for him all those years, so after dinner I was always running upstairs to write down something he told me, or call the insurance company for a patient.” She mentions that her New York friend, who’s divorced, would always say, “Come sleep over with me!” She added, “But I don’t do things like that.”

Me: “Why?”

“Well, I think he did keep me for himself. What you say is right. He was, and is, a very demanding person, and he always made me feel that my first obligation was to him. And I guess I encouraged it, to some extent. I always left a meal for him. He never had to go to a store and buy something, or figure out certain things, because I took care of them. He never would have taken an apartment in New York and been away from me for all the nights Dan is away.”

Here she was referring to my husband and the small apartment we bought together in New York a few years ago, when he needed to be there more for work. Sometimes I go with him—I have work and friends and colleagues there—and sometimes I stay at our Massachusetts home with our dogs. This is a living arrangement we both chose and both love; after almost three decades of being a mother and wife myself, I have back the solitude I crave, along with a loving family. But I think it’s interesting that my mother sees it as Dan taking an apartment, and being away from me—as if the choices were all his. I decided to not try to explain this.

“How about,” I said, “when he yells at us, or talks over you on the phone? How do you feel about that?”

“He’s very nasty about the phone,” she admitted. “But he thinks that anything I do with the children, he should be part of. I don’t agree, especially because we have three daughters, and I’m their mother, and I think I should be able to talk to them without him listening, but—it’s not worth the fight. If I mention to him some detail you told me on email, he’ll say, ‘How do you know that?’ He’ll say, ‘Why are you emailing Cathi separately? Why do you keep things secret?’ He doesn’t like anything kept from him.”

I nodded; no big news. But she had admitted it’s “not worth” fighting him to have access to her daughters—or anyone else; that, point blank, she chooses placating him over talking to us. I knew that, of course. But it helped to hear her say it now, officially.

“And when he decides what all your trips will be, or what movies you’ll see,” I said, “are you relieved, on some level? Is it better for you not to have to make all those choices?”

“I’d just rather not fight with him,” she said again. “He’s difficult, and it’s a challenge to always have to comply with his decisions, but it’s much easier to comply than to fight. To me, those things really don’t make much difference.”

I thought of her family then, especially her father: a small, warm, gentle man, round face, light-brown hair all his life. Close to my mother, her two brothers, and all his grandchildren. I remember, when we slept there, waking him at five or six in the morning to watch cartoons with my sister and me, something we weren’t allowed to do at home. He was always game. Unlike my father’s parents, my mother’s parents, Mac and Sylvia, never got angry—at us, or, that I saw, at anyone. Once, when I had an itchy mosquito bite, Mac told me I should try not to scratch it, that I should simply accept that it would itch. I found that mind-boggling. He was trained as a lawyer, but when his father died, instead of getting to practice, he and his brothers took over the family dry-goods store, which employed all three of their families for a long time.

“Do you remember your first fight with him?” I asked my mother.

“No.”

“Do you remember when he sent you to drag me out of that high school sports competition, in front of everyone, because he was furious I wasn’t home when he got home for dinner? Did that bother you at all?”

“I don’t remember that, but I’m sure I was upset.” I pictured her walking around as she talked to me, wiping the kitchen counter, straightening the endless piles of newspapers and magazines my father insists on keeping. “There was no question he was the rule maker and the decision-maker, the disciplinarian and the provider,” she said. “But I took on all the things I did as being what I was supposed to do, and I didn’t question it. I felt I didn’t have a choice.”

“Maybe,” I suggested, “in some ways it was a relief to have him do the disciplining of us?”

“Well, I just thought he knew how it had to be. I deferred to him. I didn’t always agree with the way he disciplined you—I always thought he was too harsh, too angry sounding. And I did tell him, but he’d say, ‘Oh, I wasn’t really angry about that.’ And I’d say, ‘But you sound angry, and that’s how people perceive you, so—that’s a problem for you.’ ”

She paused. “But you know, Cathi, he also was very involved in the athletic pursuits of all of you children.” This is true. When I was young, he threw the baseball with me, and, later, with my brother. He played tennis with me almost as much as I asked, which was a lot. He taught me to be tough. “And he’s extraordinarily nice to—” She mentioned a close friend of theirs whose husband had recently died. “He picked her up and took her to dinner with us last weekend and then drove her home, and she really appreciated that. He’s very loyal to old friends.”

Again, fair enough. “How about when he fought with the tour guide at that national park?” I asked.

“I was really mad,” she said. “I felt trapped and humiliated and angry. And I did say something to him about it, but he didn’t see it my way at all—and he still doesn’t. To this day. A friend recently went on that trip and he was talking to her about it and describing that tour. He agrees he was obnoxious, but he feels the tour guide deserved it, that he wasn’t getting out of the trip what he’d paid for, so he had a right to complain. I felt— I mean, he said ‘Fuck you’ to her [the guide]. I don’t really think that’s the way to ingratiate yourself with fellow travelers.” She paused. “But honestly, I don’t remember all these little things! Not until they’re brought up again. And I do think it’s a healthy denial that allows my marriage to continue.”

I nodded. I have noticed that in many, if not all, longtime marriages, there’s both pragmatism and some (healthy?) denial. “And how about when P [my daughter] left college freshman year?” I said. “Do you remember the way he reacted?” I refreshed her memory. Dismissing the opinion of P’s therapists both at home and at school, who agreed she should take time before being there, he wrote irate, condemning emails to both her and me, calling her a spoiled brat and demanding I force her to stay. “Are you gonna let her control you forever?” he yelled at me, and to her: “Will you ever let your brother have his turn for attention?” As if taking a leave from college was a ploy by her to be the queen of our house—just as he was king of his.

“I think he thinks you should discipline your kids more sometimes,” was my mother’s answer, “the way he did you. He didn’t support you when you let her leave college, but he’s very happy with the result.” Of course he is. After a year of working and figuring out some things, my daughter returned to school and excelled, graduating recently—one year late—with friends, accolades, and job experience she wouldn’t have had if she hadn’t taken that year. My father came to her graduation, beaming. All was as it should have been again.

“And you?” I asked my mother. “How did you feel at that time?”

“I was worried about her,” she said, “and it seemed you thought it necessary for her to take time off, so I thought— I mean,

she’s your child. I thought whatever you thought the best way to deal with it was what we should support. I’m sure I told him that.” I remember her staying utterly silent on the topic, though who knows what she said behind the scenes?

I asked her about my youngest sister, Amy, a successful executive who started and runs a think tank of thirteen, and with whom my father also fights—for a while now, I think, more than with me.

“He’s very proud of Amy and her work,” my mother said. “He thinks she’s very smart.” I laughed. Smarter than I am, of course, as her SAT scores were higher and she went to Cornell. “And he thinks she’s a good mother and wife,” she added. “I think he’s sorry when he has episodes with Amy.” She paused. “And with everyone! But he doesn’t want to take the blame.”

This is true. My father almost never apologizes. The only thing I’ve heard him express real remorse for is “letting” my brother move to San Diego for graduate school in his twenties, because San Diego is where his accident happened. If only he’d been close to home, the thinking likely goes, my father could have watched over him better.

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About

What My Mother and I Don't Talk About